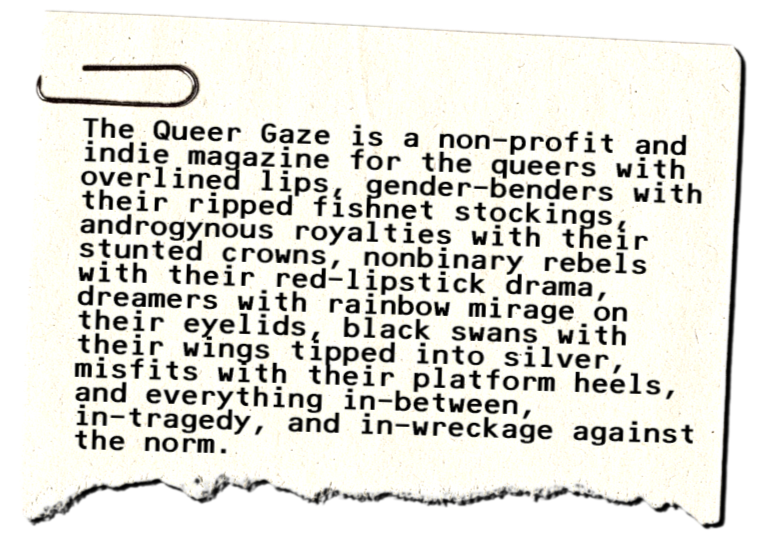

The Queer Gaze is an experimental fusion of the eccentric and eclectic, emblazoning literary sensibility with a forefront telos of innovative storytelling. Based on its name ‘queer’, it splatters a contrast against the irony; it crafts a paradoxical presence of broadening writing into an innovative ubiquitousness. Its gaze is refracted into neon colors, scattering mirrorball effervescence of the saccharine, vicious, dauntless, and vulnerability. It tremors. It seethes with rage and fangs. It tiptoes into an arabesque of nuance. It is rainbowy flamboyance with a wink of mercurial. It is the grind of teeth against shards. The Queer Gaze aims to be magnified in its whole unapologetic queerness and acerbic glam.

‘The Queer Gaze’ is a dawning of realization that amidst all the conformity, society still brandishes queerness as something monstrous, and the only way to understand the realm of this experience is looking through the ‘queer gaze'. Our literary magazine aims to exemplify spectral voices, the all-encompassing aspects of inclusivity, and the nodal of stories waiting to sprout from their dormancy. It is a punk-frankenstein that has a surging heart for binary disruption, redefining what it means to be queer. It surges to amplify empowerment, yanking the robust literary existence from minor communities and marginalized spaces. Inspired from trailblazing theories of gender and identity, The Queer Gaze aspires to be a ferocious shrapnel against barricades of oppression. It is a glitter-spiked voice for the underrepresented. It is a quiver of individuality. It is a seismic force for revolutionary dialogues.

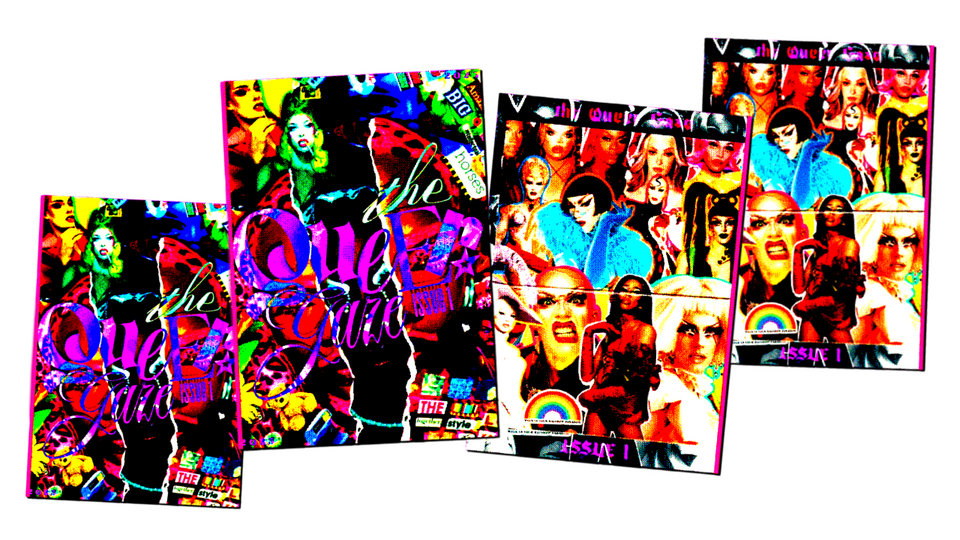

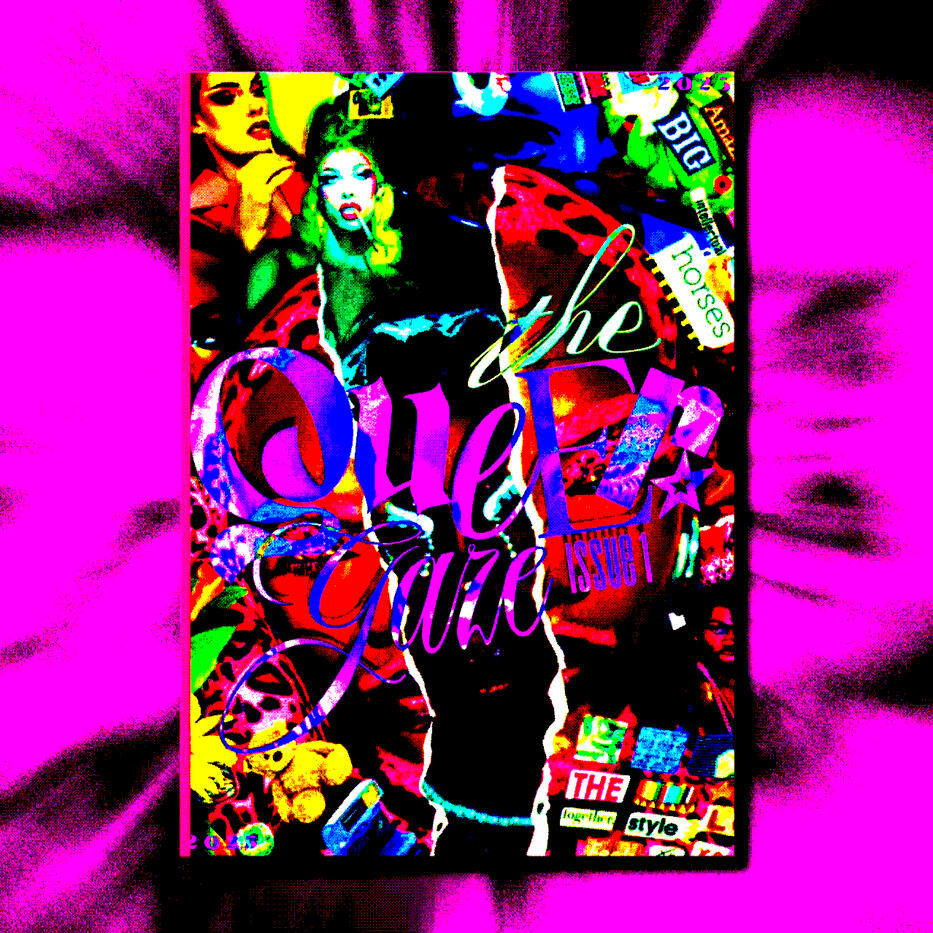

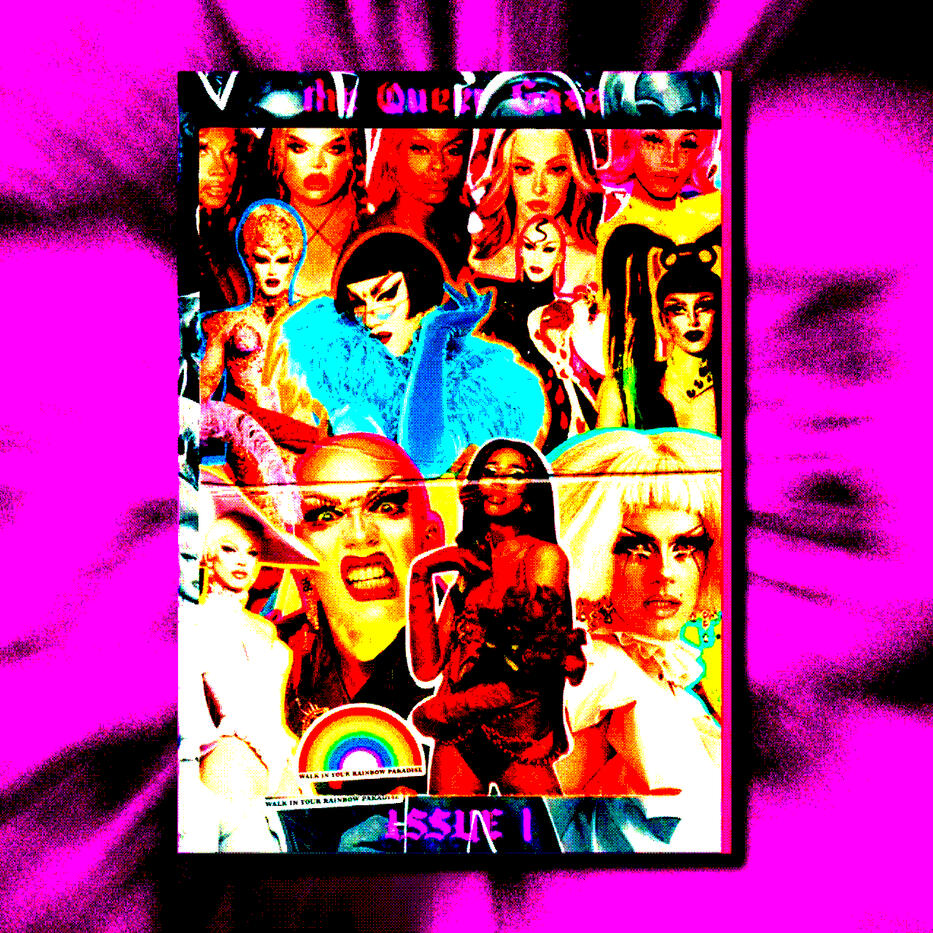

Issue 1: The Queer Gaze

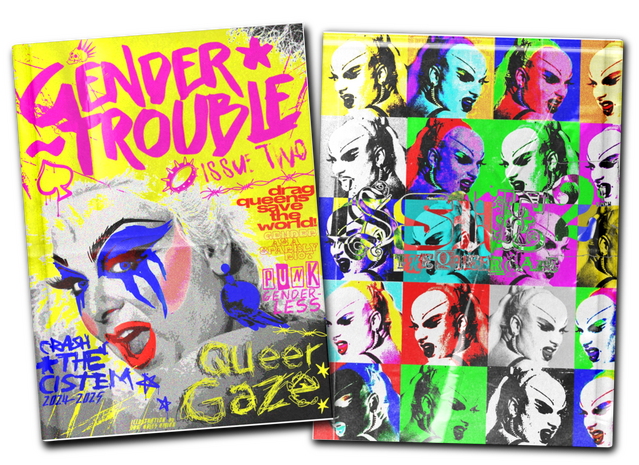

Issue 2: Gender Trouble

Submissions for Issue 3 is finally open, beeyotch! ✮ ⋆ ˚。

Queer Monsterx calls for works electric with homoerotic tension, so charged it fractures the binary and slashes through the worn-out, clichéd narratives that tether transness to "deviation" from the norm. This is a reclamation of bodies, bodies, bodies. A sharp and glorious blade in glittering hands, ready to carve through societal platitudes. It’s the glamorous knife ready to gut the notion of "otherness," a lethal claw tearing through the candy-sheen, bubblegum prom queen’s dress, rupturing lesbianism and bisexuality into unyielding royalty.It’s the horror of being viewed as prey through the toxic male gaze—the seduction and the entrapment of it. Queer Monsterx is the horror that isn’t afraid to bite back, to feast, to be unapologetically monstrous. It’s Frankenstein’s queer creation, a freak femme fatale diva dripping with power, with teeth that don’t need to be hidden. It’s the blood-dripped beauty of vampires with a thirst that isn’t for salvation, but for domination. It’s the restless, vengeful ghosts haunting the spaces where they’ve been silenced, the poltergeists smashing heteronormative walls.It’s the devil in a fur cape, an unholy temptation, ready to feast on purity. It’s the final girls, no longer the virginal survivors, but the hungry, bloodied, and vengeful queens—ready to devour their killers, cannibals gluttoning their way into destruction.Queer Monsterx is the horror of queerness, the grotesque turned divine, a siren's song calling forth the darkness, not as something to fear, but as something to embrace. It's gothic allure, the creature from the black lagoon rising up from the depths of repression, swallowing everything that is gay in its path. It's the mummy, wrapped in layers of expectation, only to unearth itself as a goddess of terror and beauty. It's werewolves howling under a silver moon, claiming their right to be wild, unapologetically, fiercely other.It’s time to rupture the confines, to devour and to become. To reclaim the grotesque and turn it into something untouchable, undeniable, and untamed. The queer monster is ready, and it’s more fabulous than ever.

Submission Guidelines

Poetry. We're seeking poems that howl under the queer moonlight, unearthing the divine in the grotesque. Whether it's an ode to a vampiric lover, a ballad of a siren’s vengeful song, or an elegy to a repressed self now reborn, explore how queerness shatters binaries and reclaims the monstrous as beautiful. Bring us verses that slash through clichés and bite back against the male gaze.Short Stories. Write us tales of queer monsters that seduce, terrify, and dominate. Create alternate universes where werewolves howl their trans power, vampires thirst unapologetically for liberation, or mummies unravel layers of expectation to reveal goddesses of terror. Think femme fatale divas with claws, Frankenstein’s queer creation, or vengeful spirits smashing heteronormative walls. Give us gothic allure and horror that devours the confines of "otherness." Limit: 6,000 words.Personal Essays. Have you ever felt like a queer monster yourself? Tell us about the ways you’ve reclaimed your “otherness” as something powerful. Share your experiences of transforming grotesque narratives into personal triumphs. Whether it's a reflection on societal platitudes or an anecdote of embracing your inner monster, this is your space to be raw, fierce, and intelligent.Other. Take your favorite icons—fictional or real—and reimagine them as queer, fabulous monsters. Craft stories where final girls become vengeful queens, devouring their killers, or where the candy-sheen prom queen turns into a feral beast dripping with power. Play with gothic themes and subvert horror tropes with audacious, queer energy.Artwork. We’re looking for visual art that embodies the essence of Queer Monsterx: drawings, paintings, digital art, photography, collage, sculpture—any medium is welcome. Capture the gothic beauty of vampires, the ferocity of werewolves, or the divine terror of sirens and mummies. Make it fierce, make it unapologetic, and make it QUEER.

Accepted Mediums

- We welcome submissions of any medium, including poetry, short fiction, essays, visual art, photography, and hybrid forms.- All literary submissions with unconventional style must be in PDF format. For literary works that follow the stylistic conventions, submit them as docx.- Images and artwork should be at least 300 dpi for quality purposes, and must be in PDF or JPEG format

Submission Requirements

File Submission. If submitting multiple pieces, please attach each as a separate file. This applies to short poems as well: one poem per file.Word Count.

Short Stories and Prose should be no more than 6,000 words. Poetry should be no more than 5 pages.Previously Published Works. We accept previously self-published material (e.g., shared on personal blogs or social media) as long as the piece fits our theme and you retain the rights.Metadata. Include your full name or pseudonym, the title of your work, and a brief artist’s biography (up to 100 words) to the form. Relevant social media handles are optional but encouraged.Submission Limit. Each artist may submit up to 10 pieces for consideration. No exceptions.